"TO CLEAN THE WORLD FROM PATRIARCHY AND FROM ALL THE POLLUTION OF THE WORLD." — MARY SZYDŁOWSKA

A conversation on maintenance between Elisa Liepsch, performing arts programmer at Beursschouwburg, and artist Mary Szydłowska on her work SOAK.

ELISA: SOAK shows you dealing with notions of hygiene, cleaning and maintenance. Often we enter spaces that are either clean or dirty – which is also connected to a hierarchy of space. But we hardly ever witness the process of cleaning. Once we arrive in the office, the cleaning, brooming, polishing and hoovering has been done, the rubbish has been taken out. This invisibilisation of labour and bodies is intrinsic to the structural capitalism and patriarchy we are living in. In your work you make the cleaning body visible, the labour and a certain understanding of what cleanliness is. Where does your interest and research in these topics come from and how did this research grow over time?

MARY: For me, this research started when I worked in different cultural institutions, mostly museums or dance related spaces. I did film documentations of exhibitions or simply spent long hours working on my other projects. I've been cruising those spaces, looking at audiences, witnessing the work of security guards and cleaning staff. All of those spaces were like non-spaces, which somehow evoke a vacuum feeling of time. This is where I got struck by the cleaning gesture, its contrast between quotidian and functional quality made towards a space which holds a strong, untouchable identity. Public spaces and cultural institutions as we know them communicate their relation to the public immediately. We take them as they are, when we enter – do we know though what care facilitates them? And is this care part of their identity and representation?

At the same time, there is never something like a clean space. I always feel that it's just a different mess and you are moving around the micro material of the world all the time. Hence the research I led since around 2017 was about this process of actually touching the institutional space through cleaning, almost like caressing.

"To clean the world from patriarchy and from all the pollution of the world."

ELISA: What fascinates you about the materiality which is very present in the work - the fabrics, tools, machines, surfaces, objects, the texture of things? SOAK is a very haptic piece.

MARY: I think it comes from a need to blur a bit the subject-object relation and look at the world through a more-than-human perspective. The material world is something that strongly informs my body, and I was interested to see how I can activate it and still cherish its autonomy. Cleaning deals with touching the materiality all the time, hence the way I partner with objects and fabrics on stage can be seen as a consequence or a fantasy on its impact on the matters. Many of those fabrics hold different spaces as well, they come from countries and places where I researched: Senegal, Poland, Taiwan, Brussels as well, and Beursschouwburg itself.

"Cleaning can be seen and experienced as a deeply subversive practice. One which allows to take over control of spaces we share, slowly breaking patriarchal patterns."

ELISA: Maintenance work always follows a certain pattern, a system that allows little alteration. Your work explores notions beyond that, there is friction, moments of anger and disruption in SOAK. Are these relating to gestures of resistance?

MARY: Maintenance is of course circular, but I've also been always looking at the very personal approaches of cleaners. I came to realise that in the activity of cleaning there is a potential to subvert the way we perceive and we experience labor. The mental space it produces in a meditative flow has no boundaries. That’s where the potential resistance lies for me. What do we dream when we work, and how it affects the gesture, its very impact. When reading Bernadine Evaristo’s Girl, Woman, Other, I encountered this character who dreamed about setting up an Army of Women Cleaners, who cleansed the world from patriarchy and from all the pollution of the world. They transform all the cleaning tools like broom sticks into weapons. In SOAK I’m researching this place of repeated cleaning and care gestures to see where it takes me. And it was taking me to a place of disruption.

ELISA: While listening to you, I think of all the unpaid and un-credited labour and care work that happens in the unseen shadows of households being done by womxn. We remember Silvia Federici and the beginning of her famous Wages against Housework from 1975: “They say it is love. We say it is unwaged work.“ Care work has always been in the centre of the feminist struggles and until today, she reminds us that this struggle is not over and the pandemic has been a good proof of that.

But I also see how the discourse around care has been swallowed up by the institutions we are surrounded by – they like to expose the care they do, and management likes to be seen as care. Because “to take care” also means “to deal with”, to create a state of normality and invisibilisation of misbehaviour, deviance and resistance through institutional power like the police for instance. Marina Vishmidt speaks of a rebrand of power as care. Does this resonate with you and what are your thoughts on care?

MARY: Yes, it does resonate. Maria Puig de la Bellacasa writes that “care is omnipresent, even through the effects of its absence”. It was important to me to research care as a verb and emphasize its physical aspect. It is carried by the readiness of a body and its presence, and maybe that allows me to differentiate it from the hijacked slogans about care made in institutional contexts. I didn’t look only at female labour though, I looked at labour of different minorities, and I researched with male cleaners as well.

"What if the cleaning I am doing, is foreseeing the future? What if the cleaning I am doing - is the future itself?"

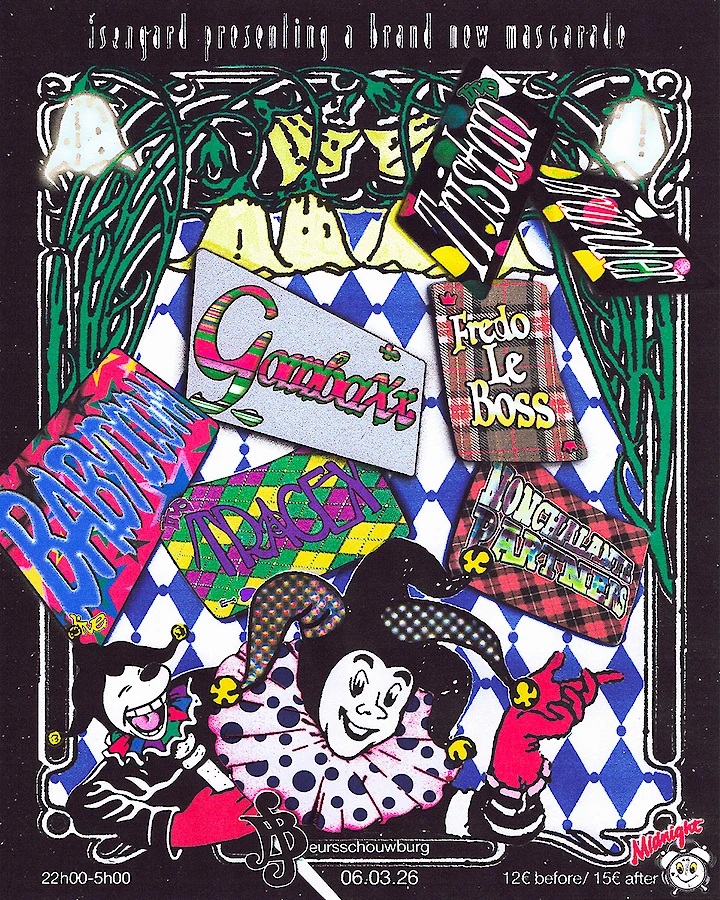

ELISA: The history of the body is also a history of hygiene. Theater scholar Ulf Otto reminds us in his research that the black box emerged from the 19th century dispositive of hygiene. The black box which embeds and disposes bodies relies on the understanding that it only makes certain bodies shine while others are being excluded – so it’s not the neutral space it wishes to be. This of course also leaves an imprint on the aesthetics that are visible or not. European theatre is rooted in an anti-bacteriological enterprise of the 19th century, so in the end, he argues, the black box is nothing other than a white-washing of art. How do you feel about being in the golden space of Beursschouwburg that shines and blinds and tries to be something else? Your work usually meanders through very different spaces – galleries, theatres, public space – what made you choose that space for the work?

MARY: I chose this space because I am really fascinated by the capacity of the cleaning gesture that is very transformative towards any space. The golden space challenges me, I wanted to see how much I can unpack it and not be tempted by the theatrical dispositive it carries anyway – the expectation of providing a show, for instance. Behind a black or golden box, a huge care work stands and moves. I am negotiating with myself how and why I want to reveal it. I’m surely not trying to represent cleaning, I'm trying to really understand what it deeply does to spaces, what its internal logic of actions are. That’s linked to very particular techniques of cleaning but also techniques of becoming invisible in space as a cleaner. It is an unstable position in SOAK, bringing in and disappearing as cleaning characters. All of them that I encountered are carried into SOAK by the gestures I learned.

ELISA: When I look at SOAK I have to think of Mierle Laderman Ukeles’ Manifesto for Maintenance Art, 1969! Proposal for an exhibition “Care”. In the 1970s she would clean art galleries claiming “my working will be the work”. Since today she holds the position of official, unsalaried artist-in-residence at the New York City Department of Sanitation. There is also Martha Rosler’s “Semiotics of the Kitchen” and many more. Do you see yourself connected to these artists?

MARY: These are very conscious references for me and I think what these works provoked within my research was the reflection on different layers of labour. Because I'm also labouring as an artist, experiencing the invisibility of that labour. There is the movie Nightcleaners by Berwick Street Collective and also a lot of lifelike references, which are very significant to me. My research is like a sponge. I take in, I take in, but not because I want to tackle them very particularly. I’d rather move along.

"What if a broom stick is a weapon ?"

ELISA: I think the battleground and groundwork of all feminist struggles lie in the intersectional and solidarian practices related to care work – especially to migrant cleaners and their struggles for better work conditions. And I like to believe that the potential for the revolution lies in the maintenance work. Maintenance as resistance, a base for a politics of transformation. Care in that sense also relates to caring for justice. That’s why taking a close look at maintenance work is such an important thing.

MARY: I agree. This lack of acknowledging working people, also within an institution is such a common thing and becomes a joke in the film The Square where the cleaning staff is actually making a mistake by vacuuming some sand that is part of an art work. I think it’s easy for an institution to excuse itself but there is always more to be done about the presence of people involved in the maintenance work. Those people keep the institutions running, not the heads of the institutions.

I would like to experience an institution which is porous and gets inspired by simple activities of care, like cleaning. It is happening already in some contexts. I think of the Museum of Modern Art in Warsaw at the moment, transformed completely into a help center for Ukrainian refugees, who suffered from Russian aggression. Also, why not look at spaces that are actually marked by the presence of cleaners? We tend to look at cleanliness as a default condition of space.

ELISA: What do you wish to maintain?

MARY: That’s a really difficult question. I will dream about it.

picture by Veerle Vercauteren